Big in Japan

In his first year of college, Todd Robertson had the same depressing moment that most artsy undergrads endure. The Connecticut-bred musician looked fearfully at his course schedule – an oppressive line-up of jazz and engineering classes – and got honest. “This is going nowhere,” he told himself. Who needs another jazz musician, he thought? Or yet another studio rat, manning boards for spoiled indie rockers and rappers demanding that their mic levels get turned up? Robertson burnt out. He didn't even last a year.

Now 34, the toy maker can't quite recall what he was up to in Boston 15 years ago. After deserting school, he remembers selling art without a vendor's license on Newbury Street – mixed medium pieces, perhaps a couple sculptures every now and then – and smoking weed. Lots of it. Some time went by, there were gallery shows, a fine arts stint, and even some success on the street-approved, app-and-mobile tech boom-financed contemporary art scene in Boston. But his collages were a metaphor for his style – a mess of this and that, some gloss mixed with some garbage.

Though not quite like Tom Hanks in the Penny Marshall classic Big, Robertson had to find his inner adolescent before coming of age. With niche and even mass market pocket dolls and action figures resonating about half way through the aughts – Kid Robot, for one, inspiring a retail frenzy unseen since the UGG stampede in years prior – the wandering painter found direction. Robertson scored some popular toy archetypes – Dunny, Munny – and glued carefully salvaged shards of trash onto them until they looked like cartoon B-movie villains. Think kiddie steampunk meets Jurassic Park.

Robertson was super into detailed toys as a kid – model planes, Transformers, He-Man, and painted vehicles from Matchbox to Micro Machines. So in the deeply fragmented and highly compartmentalized world of art toys, he quickly gravitated to a style of figurine dubbed “kaiju,” which essentially translates to “cursed monster.” Kaiju is a subcultural staple that dates back decades, with Godzilla being the most famous crossover goon of all. Robertson was familiar with some of the characters – he'd watch them on Saturday cartoons as a boy. But he knew nothing of the nerd dimension that awaited him.

With his early toy experiments selling, before long Robertson became known as the Dr. Frankenstein of kaiju, tweaking and reanimating plastic monsters in any way his warped imagination wished. Though jazz, sound engineering, and even more traditional artistry proved too difficult to make a living off of, by 2009 Robertson had ventured deep into a new career of creating – and, on occasion, even playing with – toys. It proved a natural fit from the jump; his penchant for hacking everything from kaiju devils to crab-like nautical creatures with scraps of old radios and televisions even earned him a handle, Mecha Virus, and a reputation to match as a promising American contender in a niche marketplace.

“When I started seeing this whole art toy movement catching on, I wanted to be part of it,” says Robertson. “The culture just kind of sucks you in.”

I meet Robertson at a sushi joint near his apartment and studio just south of Boston. It might not be intentional, but his restaurant choice is right on theme for a white guy operating in a Japanese world. As he picks at his bento box with precise clicks of his chopsticks, Robertson tells me about his first trip to Japan three years ago. He financed it with a settlement purse that he won from a lawsuit against a cab company; while using a crosswalk, he'd been bulldozed by a taxi with extinguished headlights. After cleaning house, Roberton bought his first ticket to Tokyo. His girlfriend at the time, a native of Japan living in Boston, came along as his interpreter.

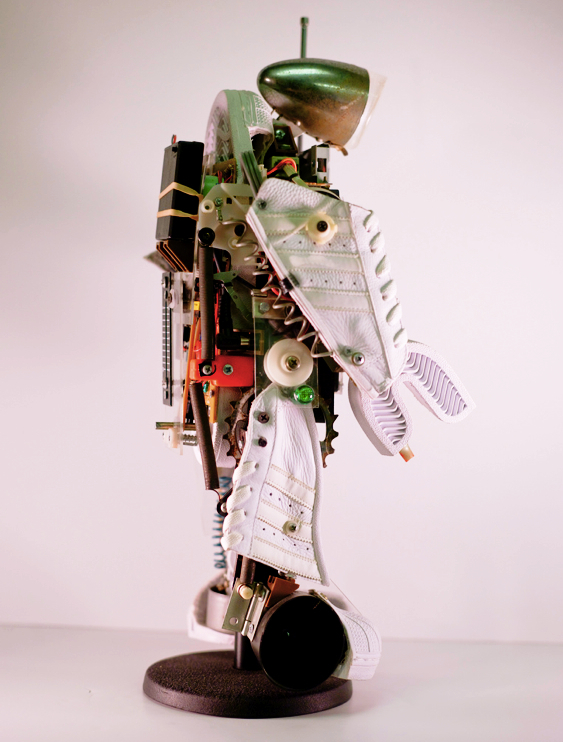

In the infinitesimally intimate, exceedingly quirky universe of kaiju hacking, the ultimate goal is to get your own toys produced in vinyl. The kings of kaiju manufacture in a handful of small Japanese factories, though some industry heavyweights hail from the United States and elsewhere. Before you have a vinyl figure you've designed yourself, there are essentially two options for base models to airbrush and add onto – mold your own toys from scratch out of resin, which is a messy process but can be done anywhere, or buy existing kaiju and have your way with them. Until recently, Robertson did both, mechanizing classic vinyl with everything from vacuum tubes to screws and spark plugs, and also shaping unique resin pieces. “The Mecha Virus,” he says, referring to his handle, “is the robotic shit that can infect any character. It's a found object aesthetic.”

The virus, as it were, has touched kaiju aficionados worldwide. There's no specific market for what Robertson does; a few stores in the U.S. and Tokyo are hip to his game, but otherwise the art toy ecosystem exists solely online, like an international nomadic hobby shop. We met for a 1pm interview. Minutes earlier, he'd put five new metal-wound characters for sale on Instagram – each selling in the $300-$500 range. By the time we finished eating, all but one of them had been spoken for.

“Some people just simply, absolutely have to have something,” laughs Robertson, who says he teases buyers while his specimens are in on the bench. “You really want to let people know that you're working – they love the process. By showing a work in progress, you're promoting, and it's not that hard to just put stuff on Instagram or Twitter . . . We're all doing this out of pocket, so we can just set up online and go direct to collectors. I often sell pieces before they're even done.”

The toy business is good for Robertson. He's been to Tokyo twice now, and heads back soon for his first gallery show there. Back home, a company in Massachusetts named Monster Kolor, which caters to kaiju, created a custom metallic airbrush paint in his name. Most monumentally, though, is the development of his debut original kaiju. Named Ammonaito, the toy is a horizontally sprawled squid-like menace, ideal for custom-fitting in whatever grotesque fashion artists may conceive. Robertson already has plans; he's been sculpting mock-up Ammonaitos in resin for months, and has a pair of painted prototypes perched in a glass case beside his makeshift cardboard fume hood.

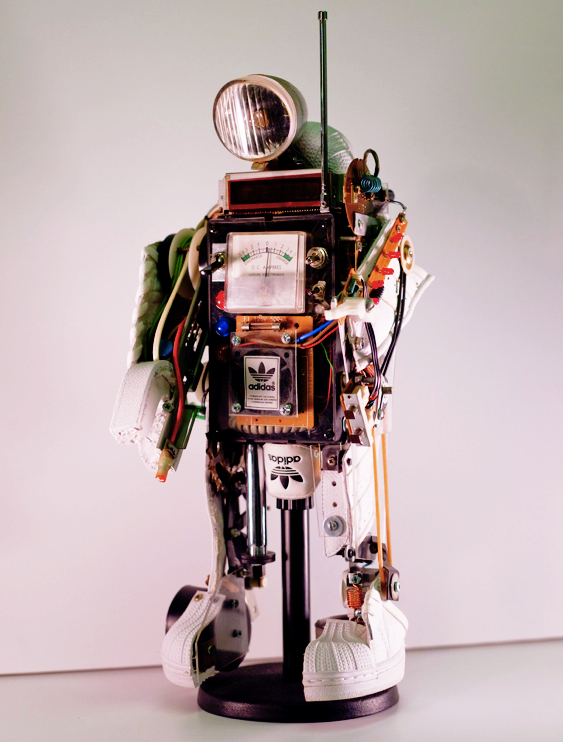

Back at the studio, Robertson shows off his relatively small collection of toys. First there's Adi-Bot, a sneaker-machine cyborg cobbled from a crisp white shell-toe and a mess of functional battery-powered circuitry. Engineered for an Adidas-sponsored art show seven years ago, Robertson credits the Adi-Bot project with setting him along the path to kaiju. Elsewhere, beside dozens of blank vinyl canvases awaiting his stroke, Robertson's shelves house his cherished stash of work by his contemporaries. He's eager to share the stories behind them, but keeps returning to the pride and joy of his own making, Ammonaito. Like a kid in a toy store, he can't help himself. He's glowing. I ask Robertson what the most coveted collectible of all is – the toy that diehards the world over would fight like King Kong and Godzilla for a chance of owning. He thinks for a moment, then answers, “I guess everybody has their own holy grail. We all have an extremely unique piece that we want.” Robertson has had a lot of toys over the years, but it looks like he finally made his favorite one.

Photography Credits

Bob Conge

James Wormser

Mark Nagata

Kaijumonster Blog

Courtney L. Robertson

Chris Faraone