Tiyospaye

When you know someone for long enough, it's easy to lose sight of how much they could have changed in the time you've known them. You lose track at times, more oft than not, of the growth that occurs naturally as a consequence of time. If you're lucky, someone close to you can change so much that their work will surprise & impress you when you take a step back & take stock of the bigger picture. Such is the case with Chloé Zhao.

Born & raised in Beijing, educated in London & the US, shifting gears from studying Political Science at Mount Holyoke to Film Production at NYU, Chloé has devoted herself, in the time I've known her, largely to one project. That project, initially entitled "Lee", became the subject of an intensive research & development process, nurtured largely by a list of awards, labs, & fellowship grants too numerous to name, amongst them prestigious awards from IFP (2014 Gotham Awards Spotlight on Women Filmmakers 'Live the Dream' grant), the San Francisco Film Society, Film Independent, Cinereach, the Adrienne Shelley Foundation, & perhaps most importantly, Sundance Institute. With a timespan of over 5 years from inception to completion & release, Lee changed shape & shifted titles (finding its official name with "Songs My Brothers Taught Me"), but never lost its essential purpose --- to document through a narrative form the lives of Lakota Youth on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the Black Hills of South Dakota. From my experience working with her in the past, it came as no surprise that Chloé would find in Native At-Risk-Teens a well of opportunity for understanding & a ripe, potent source for narrative.

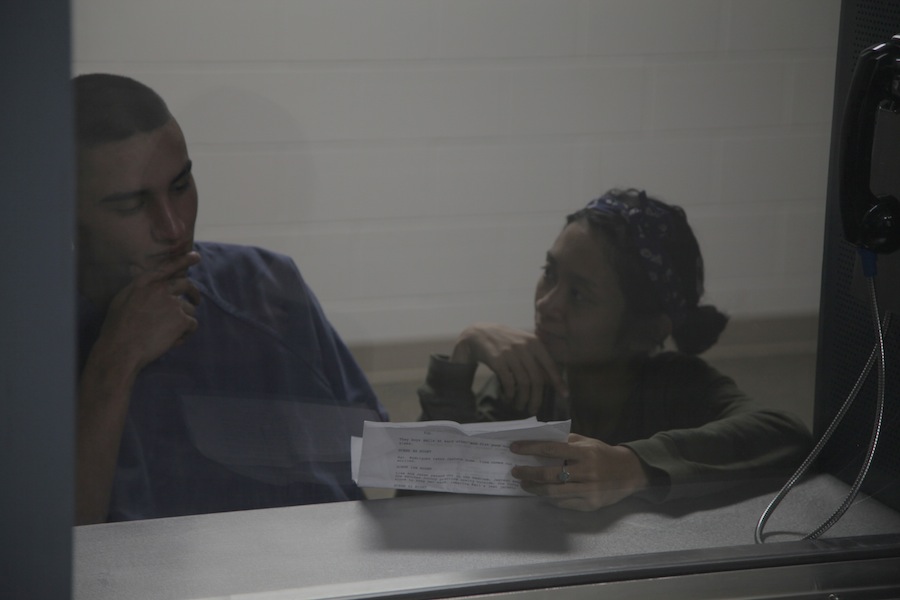

Songs, as it's referred to consistently throughout our conversation, is something of a visual revelation, to say the very least. A precision & delicacy of form pervades every frame, all the more astonishing when considering the film was captured with virtually no camera department or support. The weather beaten colors & textures of Pine Ridge & its citizens are luminous & vibrant, no matter how aged or faded --- almost ecstatically so at times. The steady camerawork, though handheld for the large majority of the picture, does not shake loose the corners of the frames so much as it rocks in time with its subjects' pace, creating a soothing rhythm --- something as human as the performers. The sound of the hills permeates every scene, the windy silence at times enveloping the young characters as they linger, oftentimes solo, set against the broadness of the Plains backdrop. We meet Johnny Winters, a young Lakota, busy at the business of Rez-Life --- hustling to survive, distributing prohibited alcohol to his neighbors, in order to support his younger sister Jashaun, & their mother Lisa (played by Pocahontas herself, renowned American actor Irene Bedard, whose performance as a woman trapped by her surroundings & culture is as livid & unreal as any of recent years, certainly any portraying First Nations' Peoples.) It is only upon the tragic death of their estranged Father in a house fire that Johnny considers for the first time exactly what their incarcerated brother has been telling him for years --- that he's got to escape the Life on the Rez, by any means necessary.

When I meet with Chloé again, it's been years since we last saw each other at Sundance. She's left the city in the meantime, spending time upstate, before recently settling in Denver, CO. In the time between our correspondence she's become a part of the Tiyospaye, or as the Lakota define it, "extended family," of several of her performers. Screening the newly completed film of Songs at the Cinereach headquarters in Chelsea, just before its bow at this years Cannes Film Festival as part of the esteemed Directors' Fortnight, it struck me for the first time, this growth that goes unseen when the notion of how long we've known someone interferes with what we think we know about them. To say that Songs was worlds beyond Chloé's past efforts as a filmmaker wouldn't be holding a candle to the accomplishment that it is, but more importantly, would be suggesting that at any time she wasn't on the road to where she is, & perhaps, is about to be. I spoke to Chloé about the film, her own process, & the road to fruition across the course of the summer & into the fall. In the meantime, Songs My Brothers Taught Me has been acquired by Fortissimo Films, released to rave reviews in France, secured nominations for the Independent Spirit Awards in 3 categories (Best First Feature, Best Cinematography --- Joshua James Richards, & the Someone to Watch Award), & will drop stateside for a two week run at Film Forum in March of 2016. We're all plenty excited for it to finally be available in the US, where it rightly belongs amongst the limited canon of films w/First Nations' advocacy at their core. To be true, it's about time.

EVAN LOUISON: We want to hear about the road to the project beginning finally, after numerous setbacks. There were considerable risks you took in choosing to shoot last September rather than waiting for Significant (actor Forest Whitaker's production co.) to finance the more considerably budgeted version you had been prepping for years.

CHLOÉ ZHAO : I was a very different person five years ago when I first set out to make this film. I thought if I had a good script about an interesting subject matter, and if I could get institutional support from places like Sundance Institute, then I would have no problem getting funding for my film. I was naive. After 3 years, labs after labs, fellowships and grants, 30 drafts of rewrite of a script I believed in, instead of living my own filmmaking fairytale, I found myself unable to find a single investor willing to make this film. My goal of shooting the film in 2013 became more and more impossible. Then I was introduced to Significant Productions, who took a great interest in the project. We tried to come up with a plan for 2013, but it was just too last minute and too rushed. Around that time I lost Johnny’s brother, one of my main supporting actors, to [a term in] state prison. It had a deep effect on my team. I also met 11-year old Jashaun St. John. I didn’t have a role for her, but decided to write one --- because she is incredible. The final push came on the day when we were at ARRI CSC in New Jersey, doing a camera test and getting ready to shoot in September. That was the day we found out we had to wait until next year to make the film. We stopped the camera test and went home. When I got back to Brooklyn that evening, I found out my apartment was broken into. All my equipment, computers, hard-drives with green screen and b-roll footage we shot for the film were all stolen. It was probably one of the worst days of my life. Now looking back, I'm grateful for that painful arrangement. If my team and I weren’t so desperate and hopeless, we would’ve never had the guts to take this risk. I decided to let go of the script and come up with a treatment we can make with 1/10 of the original budget and make it happen in two month. South Dakota weather is extreme, & there is only so much time you can shoot each year. To give an example, our first week was 105 degrees and our last week had one of the largest snow storms in South Dakota history --- and we only shot for 6 weeks. I was very fortunate that my team all agreed to this madness, & that they had all spent enough time on Pine Ridge with our young cast to understand why I had to make this difficult decision. After the shoot, I edited together scenes to show Forest and he gave me advice, his company funded our post- production and has continued supporting us as the film goes out into the world.

EL: Could you outline what it felt like the first time you visited the Black Hills, one of the most fascinating aspects of this whole project is your connection to the Lakota people, & their struggles.

CZ: At first it was a feeling I couldn't understand. Fear, maybe. I remember driving from Denver to Pine Ridge through Nebraska for the first time with one of my producers. Once on Pine Ridge, we decided to take a short cut that wasn't on the GPS. We ended up on a dirt road, in pitch black, with nothing for hours, except the ghostly white walls of the badlands and the eyes of animals being lit up by the headlights. The next morning I walked out of the motel and saw the plains for the first time. There was still fear, the fear of the unknown, but there was also a release, a sense of freedom. For the next five years, I've driven between Pine Ridge and New York countless times. And every time I cross the South Dakota state line, that feeling of release and freedom never ceases to inspire me. On that first trip I also went to some of the roughest parts of the reservation. The contrast between the devastation and the beauty was something that left a deep mark in me, which I think years later made into the film. Every person I met had a story that fascinated me. Though I was interested in learning about the traditional culture, I found my deep focus in how young Lakotas live their lives today, and all the pains and pleasures that come with being the young heirs of this ancient land.

EL: John Reddy seems like he’s grown up so much right in front of you, & so much of his life must have changed while you were collaborating on this, all the way back to “Lee.” He was so raw, wide-eyed & unformed still when I first met him in 2012. Now, watching the film, he seems so at home in front of the camera, as if the two of you became like family in order to capture this truth of what life is like there. Was that your experience?

CZ: Very much so. It would've been easier in someway if I were just his director. Because some distance is healthy for the director & performer to have. But John became the heart of the film and he became irreplaceable, because I had changed the script so much to incorporate what I've learned about him in real life. So when I had to let go of that script, it was okay --- because the heart remains. But If I didn't know him the way I did, I wouldn't have been able to build a film around him without a script, and he would've never allowed me and my camera into his life like that. He thinks 80% of the character is who he is in real life. We do argue and I used to tell him off. Now I have to do it differently because he is 20 now and I can't treat him like a child anymore. (laughter)

EL: Jashaun & you have a serious familial relationship as well, to this day. Does the concept of family factor into how you conduct yourself as a filmmaker?

CZ: I've always lived in big cities where even neighbors don't talk to each other. I rarely see my family. I think being on Pine Ridge, where everyone is related, and everyone is always saying 'Hi' to everyone, it became contagious. You are expected to act as part of the community. If you just take your film crew to Pine Ridge, make your film and leave, then you are depriving yourself the chance to experience a new way of life. Sometimes it could be frustrating because I didn't understand why people would do things a certain way, or how our political views differed so much. Sometimes it was painful... But without that immersive experience, I would never have been confident to make a film about a place that I'm not from. Being a part of a family is a disillusion process. Because when you are with family you know all their flaws and mistakes, you know who they really are behind the masks. All the illusions I had about a place like Pine Ridge or about Native Americans, courtesy of our mainstream media, were gone by the time I was making the film. That was very important to me.

EL: You & Josh (Richards, cinematographer] seem to have developed a tight working dynamic, where you were able to create images whose vast scope were created with at times, not many more eyes besides yours. How important does it feel to cultivate this resource in your work?

CZ: Communication during an artistic collaboration is a very intimate and private process for me. It's an one-on-one interaction. I don't like to speak out loud to my actors in front of people. I feel the same way with Josh. A lot of the time during this film it was just my actor, Josh, my sound recordist and myself. That was it. I didn't have my own monitor. I would just look over Josh's shoulder from time to time and whisper what I needed. Without a lot of trust in him, I could not have worked the way I wanted to with my actors. It was so important to me on this film, because I wanted my actors to know as little as possible, in order to keep them in the moment. To achieve that I rarely rehearsed or did any blocking. So I had to rely on Josh to think on his feet and trust that he knew what I needed.

EL: How does writing something for so long, that goes through so many iterations & so much revision, & only at the last minute becomes largely discarded for a more free, metaphysical narrative, documented largely w/a limited number of hands, become something that you walk away from as a writer? At what point does the director side of you have to step in & say, “Now, This” instead of what you devoted so much your heart & time to?

CZ: I will admit that one of the biggest weaknesses of the film is its script --- or the lack thereof. I came up with a treatment less than two weeks before shooting. I wrote every morning based on what I got in the can the day before, hoping in the end we could find a coherent story in the editing room. I spent three years wearing the Writer's Hat working on a script I had to let go. I don't regret it because it was three years of screenwriting education, mentored by a lot of amazing screenwriters and directors. I thought I had a decent script. But part of me also felt trapped by that script because of all the new, interesting characters I met on Pine Ridge. Looking back it was a delicate balancing act, one that I had so much more to learn about --- when to steal away from the story, and when to rein it back. I made a lot of mistakes I later realized in the editing room. I hope that next time the director side of me speaks up more during the writing process to keep the blood fresh, and that the writer side comes out more often during filming to keep the director from getting on a wild horse and charging off...

EL: The problems on Pine Ridge seem like the problems of any urban or rural indigent environment, only magnified by a thousand. Is there anywhere else in your history that you’ve seen such struggle & potential & felt so connected to it?

CZ: I was a teenager growing up in Communist Beijing, in the early 90s when China really opened up its doors. We went from studying Mao to MTV overnight. As a teenage girl whose hormones were going wild, it was a mind fuck. I couldn't turn to my parents, who went through the cultural revolution, for answers. I couldn't turn to my teachers or my government for answers. I didn't trust anyone. I just wanted to get out. In that sense I can identify with Johnny and Jashaun's generation. Their parents' and grandparents' generations went through boarding schools where their cultural identities were taken away, that in turn echoed what my parents went through during the cultural revolution. Their parents, like my parents, never had internet growing up. The "fish tank" they lived in was covered up. That cover was lifted off for me when I was a teen, as it was for Johnny and Jashaun. I understand what it was like to come-of- age feeling confused, trapped, and to experience a severe identity crisis.

EL: Growing up in China, & then going to school in London, you had a storied existence from the very beginning, & had to have acquired your worldview as a result. You’ve told me previously about your desire to be in a place that isn’t New York or LA. Talk about this, & what the Plains seem to hold for you.

CZ: I think a lot of us have experienced the side effects of the fast-moving, ever-expending, ego-centric world we live in, where humans had "conquered" nature. We can do whatever we want: We are carving out the earth, making it into something comfortable for us, and not caring about the consequences. As a film director, I used to think that my own vision was the most important thing in the world, and that I was destined to make that exact vision into a reality, whatever it takes. It's a lot of controlling what we have to do as human beings... What we are doing to the environment, to each other, and to ourselves. As result I think we are plagued with anxieties which we can't even explain. Going to the Heartland was therefore a very crucial step in my life. It was uncomfortable in so many ways, and forced me out of my comfort zone. When the wind picks up and the storm clouds start to gather, you better cancel everything and go inside. Your vision doesn't matter. The priorities in life are different here. It forces you to get out of your own head and, for lack of a better word, survive. I guess when you live close to the land, you are often being reminded of your own mortality, which is sometimes forgotten or denied when you think you are above nature. It's humbling. It's necessary. It’s freeing. I just moved to Denver. I'm not ready to live on a ranch on the Plains yet, but I'm glad it's only a short drive away.

SONGS MY BROTHERS TAUGHT ME plays March 2nd --- 15th, 2016 at Film Forum

All images © 2015 Highwayman Films