My Black Angel

Aïda Ruilova’s rhythmic, visceral short films & video work are both culturally and self-reflexive; exploring the cycle of influence and obsession that feeds into creating a work of art. An ode to the slasher genre, a love letter to an erotic exploitation auteur, passions expressed by an aging movie star, and an exploration of a legendary film maker’s own idols are all subjects in Ruilova’s work --- revealing the layers of inspiration and fetishism that bind an artist with their creative precursors. By injecting her own strongly realized sensibilities and references into these pieces, Ruilova is offering a highly personal insight into how the cyclical relationship of influence and admiration informs one’s own creations.

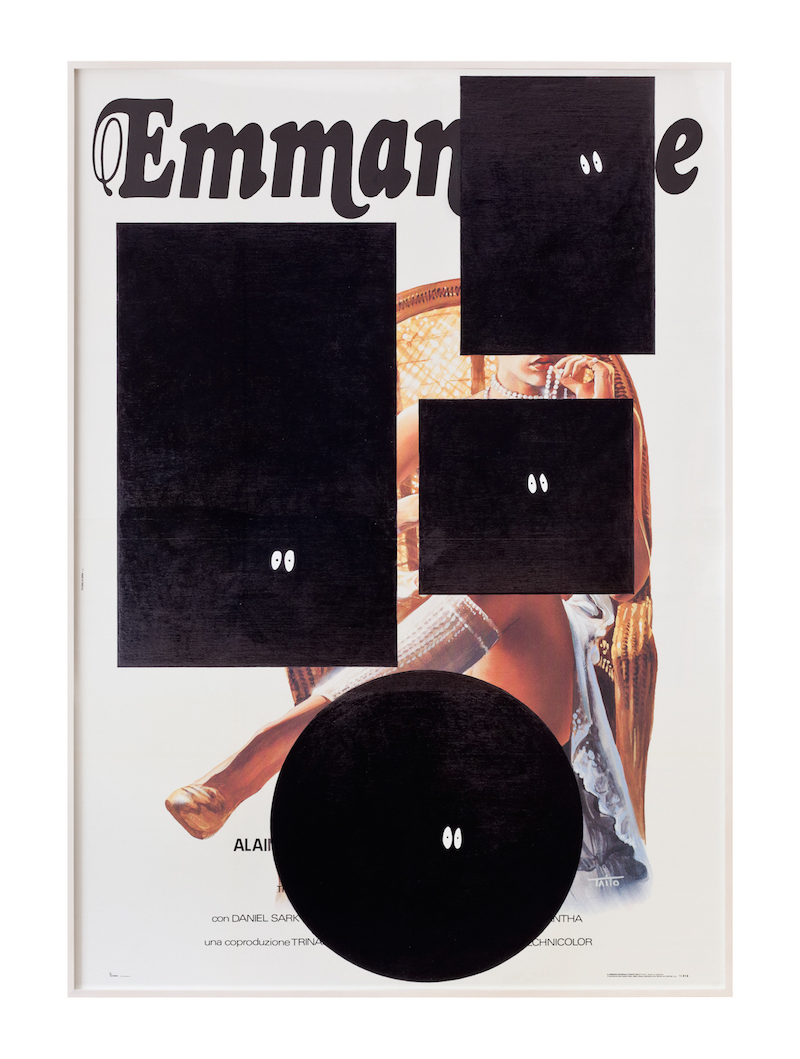

Emmanuelle, 2013, Pencil and oil on paper

Rémy Bennett: In your film Head and Hands: My Black Angel you are documenting Abel Ferrara paying tribute to [Pier Paolo] Pasolini and Zoe Lund [screenwriter & actor, Ms. 45 (1981), Bad Lieutenant (1992)] by him telling stories about them as he is in the process of developing his own film about Pasolini’s death. Through his storytelling, Abel’s own character is being revealed, and we are simultaneously seeing a portrait of Pasolini, Zoe Lund, and Abel Ferrara and in as sense you as the director. At one point Abel speaks in relation to how making a film about Pasolini could somehow inject some of Pasolini’s craft and artistic spirit into his own work. Was that Russian doll effect of homage something you set out to experiment with in Head and Hands?

Aïda Ruilova: When I first reached out to Abel I didn't know exactly what we were going to do together. I did know that I was a fan of his body of work and in turn him. I was also obsessed with Zoe Lund and her story, and really impressed that she wrote the script for Abel's film Bad Lieutenant, which was the type of film I assume would have been written by a man. It took about a year for me to have an understanding of what I wanted to do with Abel. Getting to spend some time with him lead me to see that Abel is such a beautiful storyteller…that essentially with just the motion of his hands his thoughts became images. I posed a question in an email to him as a starting point for the film which was: 'Please speak about Pier Paolo Pasolini's death and how would you direct your own death scene in relationship to his?’. I shot with Abel once a month for five months, and as he spoke about Pasolini's death and the crime involved, Abel's own story came through, and the film transformed into a portrait of both directors’ lives and work. I often feel like I’m embedding myself into fellow collaborators’ bodies of work when I start working with them, and I do fall in love with them at certain points throughout the process. Its inevitable since its something you care so much about, but it’s a romance that has more to do with creating a love letter to the medium.

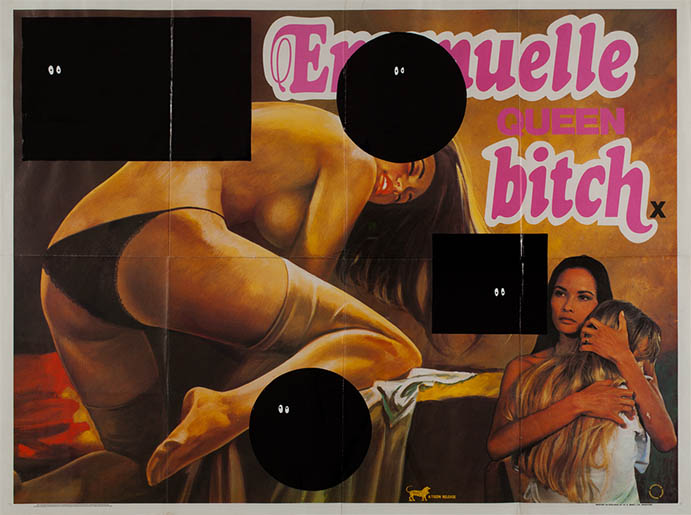

'Emanuelle Queen Bitch,' 2013, pencil and oil on paper

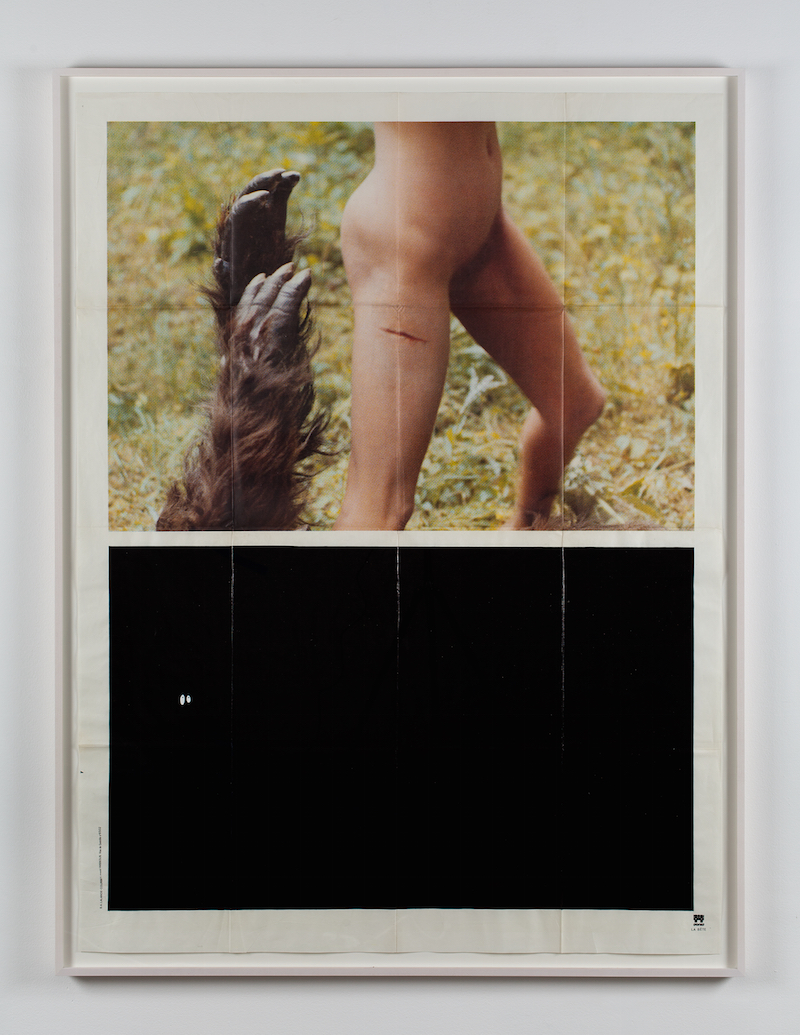

RB: In a way all great movies are like love letters to the medium itself and to a film maker’s own predecessors. It’s an art form filled with a deep exchange of appreciation that you capture in your work. The significance of artists having creative heroes and the importance of shining a light on your own artistic idols is something that you deal with time and again; whether it’s creating art through repurposing vintage cult movie posters like you have with films such as Emmanuelle and The Beast, or honoring underground cultural icons.

AR: I’m a lover of the medium. I love movies and the history of movies. I seek out people whose work I admire and who are important to me. Pasolini's death has always been linked with conspiracy stories and his ending felt a lot like one of his own films. Abel's body of work which came out of porn and exploitation had such strong ties to a certain time in New York City, and his later films are so important in the canon of genre film. They also have a very personal vision to them. Both of them are extremely unique voices in film and people I admire and look up to.

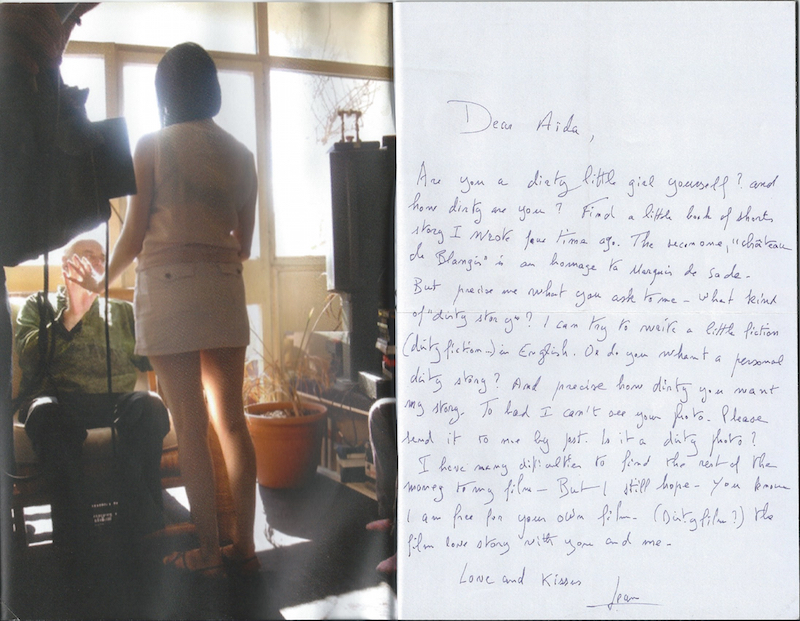

Still from Life Like, 2006

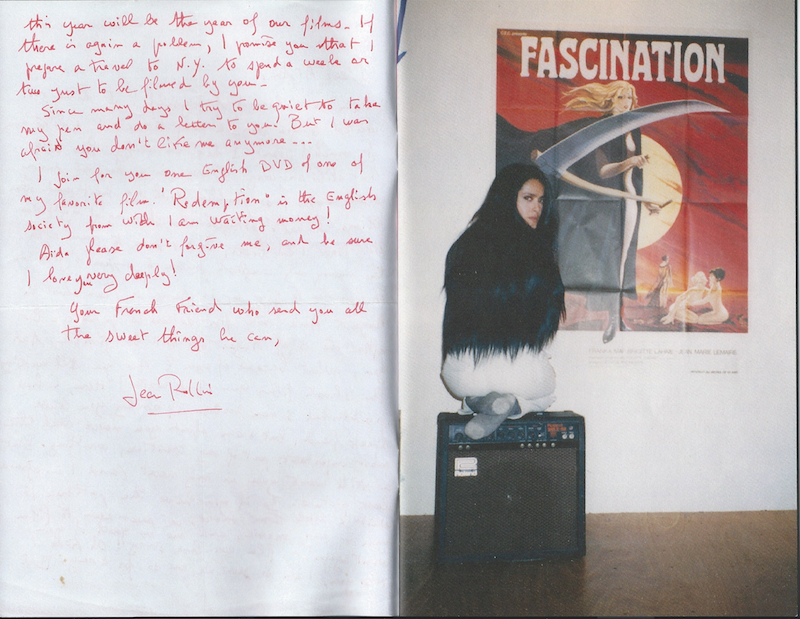

RB: I would love to talk about your projects with the French director Jean Rollin. Your film Life Like which is an homage to Rollin has been referred to as your pinnacle of reflexivity. His aesthetic obviously had a big impact on you. It’s pretty magical that your admiration eventually turned into a collaboration between you both. When did you first become aware of his movies?

AR: I had first seen his film stills in a book and then I sought out his work. The majority of his movies are genre films and mainly Vampire stories. Jean made hard core sex films to finance his own personal films which were more soft core and erotic and had a very personal vision.The way they moved felt like these long visual poems that were laced with sex and death. They’re slow moving…almost trance like; combining his childhood fascinations with American cliffhanger serials and early 20th century French Fantastique, with soft core sex and poetic dialogue. I initially made a connection to him by contacting his son through a website i found online, and I ended up visiting Jean for the first time in 2001 where I shot a short video with him in his home in Paris. After that we began writing letters to each other which eventually lead to me shooting another short film with him called Life Like.

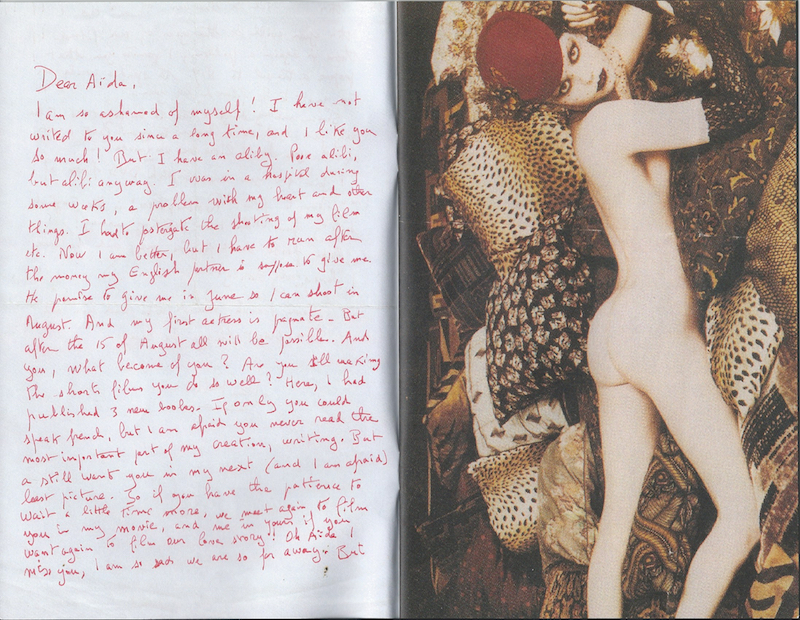

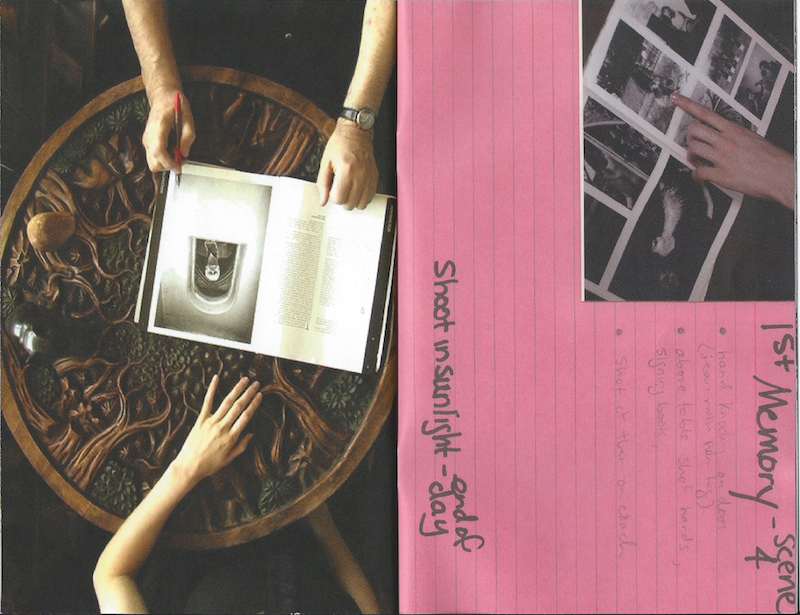

RB: You eventually made an artist’s book out of your correspondence with Rollin. In his letters he expresses so much genuine love and appreciation for you as a friend, and as a collaborator. How was the deeper nature of this connection forged?

AR: I just finished a collection of artists’ books of my films and I made one for Life Like. It has a selection of the letters we shared along with images he sent me, and stills from the film we made together. Jean was a total romantic and the letters became a space where we could play out our affection for each other. Letter writing lives in its own unique time and the distance between us created a delayed sense of desire. We both enjoyed playing muse to each other…it was a mutual appreciation.

RB: In your film Meet The Eye, two characters are participating in a steamy, nightmarish exchange within a bedroom, played by the actress Karen Black and visual artist Raymond Pettibon. By casting Karen Black you were inviting a number of associations for the viewing audience right off the bat due to her cultural resonance and place in cinematic history; once again adding a layer of reflexivity. The same could be said in relation to the casting of Raymond whose illustrations often depict cultural icons from the likes of Mickey Mouse or Joan Crawford to Charles Manson and Jesus. This seems to be in a way integral to the overall effect of the piece. How did this casting pairing come about?

AR: I had been commissioned to make a new work for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles which meant that the piece had to be LA based. I’d been watching a lot of The Twilight Zone as inspiration at the time and I wrote a script that featured a couple that had a ‘noirish’ feel to it. Karen Black was someone I contacted right away because she is such an exceptional actor and an icon of 70's cinema. She was actually the first 'professional' actress I worked with…before that I usually worked with friends or people I met on the street. I decided to have Raymond Pettibon play opposite her because I liked the tension of pairing a visual artist non-actor with an established actor.It made their rapport in the film more disconnected which is what I was going for. It was also the first time I wrote a full script, so having them act it out was a dream for me.

Stills from Goner, 2010

RB: In your film Goner a ‘final girl’ - type young woman is trapped in a room with an invisible assailant who violently attacks her. The piece is an examination of the horror genre as a whole. After watching this and the erotic vampire films that have informed your work, I wonder how much this genre has impacted you and your artistic sensibilities throughout your life?

AR: The first film my father took me to see was John Carpenter's The Thing. I was only 9 years old at the time and I can remember covering my eyes a lot. I liked that film could affect me that way…[that it] could manipulate my emotions and put me front row with my fears. I think I've always liked exploring the mechanics behind creating certain psychological spaces. Making Goner was a new process for me because when shooting and simulating violence it has to be so mapped out. The process in no way matches the final product since it’s so mechanical to produce that effect in the viewer. With Goner I wanted to make a work that gave people the money shot…meaning very little story and just the physical act. Stripping the genre down reveals a lot about its inner workings and makes you question what effect it is having on you the viewer-and why.

The Beast, 2012, Pencil and oil on paper

Aïda was a nominee for the 2006 Hugo Boss Prize.

Her work has been featured in the 50th Venice Biennale, the 2004 Whitney Biennial, and the 4th Berlin Biennial,

as well as Tate Britain, London, ZKM, Karlsruhe, The Kitchen, NY, and the Museum of Modern Art, NY.

All Images Courtesy of the Artist, All Rights Reserved.